Piano Sonata BB 88 (SZ. 80)

I. Allegro moderato

II. Sostenuto e pesante

III. Allegro molto

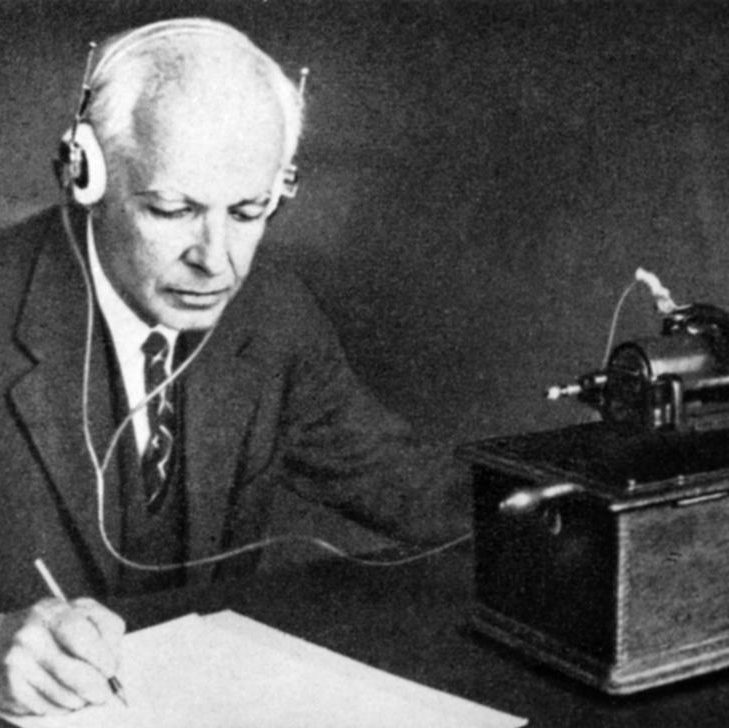

Hungarian composer Béla Bartók dedicated much of his life to the study of folk music. Both he and his friend and fellow-composer, Zoltán Kodály, are considered to be among the first of the modern ethnomusicologists. In 1906, equipped with an Edison wax cylinder, they began spending summers in the countryside collecting Hungarian and Transylvanian peasant songs. Bartók soon incorporated this rich collection of folk material into his original compositions, and it was through this extensive research that he was able to find his voice as a composer. In subsequent years he developed a personal folk-derived language into a musical idiom that would be unique among twentieth-century composers.

One often forgets that Bartók was a pianist of formidable talent. Before gaining recognition as a composer, he began his musical career as a concert pianist and professor at the Liszt Academy in Budapest. His Piano Sonata was written in 1926, the year referred to as his ‘Piano Year’, in which he also created significant works such as his first Piano Concerto, Out of Doors, and his Nine Little Piano Pieces. These works not only served as original material for his own concerts, but also as a platform to explore compositional techniques and devices that tested the limits of the piano, while creating music rich in mood and character — from the lyrical, to the declamatory, to the percussive.

The Piano Sonata, Bartók’s sole venture into this medium, was written at a time when he was absorbed in the study of Renaissance, Baroque, and Classical forms. The first movement is externally characterised by a driving ostinato, pungent dissonances, and an inexhaustible array of rhythmic inventions and drumming effects. The internal structure, however, carefully follows principles of the Classical sonata form, in which themes are constructed by motivic development. The second theme, a folk-flavoured melody, provides a humorous and songful contrast to the primitive dance rhythms. After a contrapuntal development section, the momentum of the recapitulation builds to a tremendous climax in a coda where the frenzied rhythms of a Csárdás break loose. The rhythms return to their earthy roots as primeval drums pound their way towards the final note: an E, the tonal centre (the “key”) of the work.

The declamatory second movement demonstrates rigorous four-part chorale writing combined with Bartók’s distinctive parlando-rubato style. In the form of a lament, it is full of strange sounds and eerie night noises; distant sombre bells and ritualistic chants. Leaving this desolate landscape, the vigorous third movement — a rondo with variations — throws us into a bustling village scene in which we hear the cheerful sounds of a peasant flautist and a village fiddler taking turns joining in the merriment. We are left with the colourful impression that these are authentic folk tunes, fresh from the fields of Transylvania, but they are all in fact derived from Bartók’s own imaginative invention.

Tony Chen Lin, 2018 (Booklet notes to CD “DIGRESSIONS”)

You must be logged in to post a comment.