Humoreske Op. 20

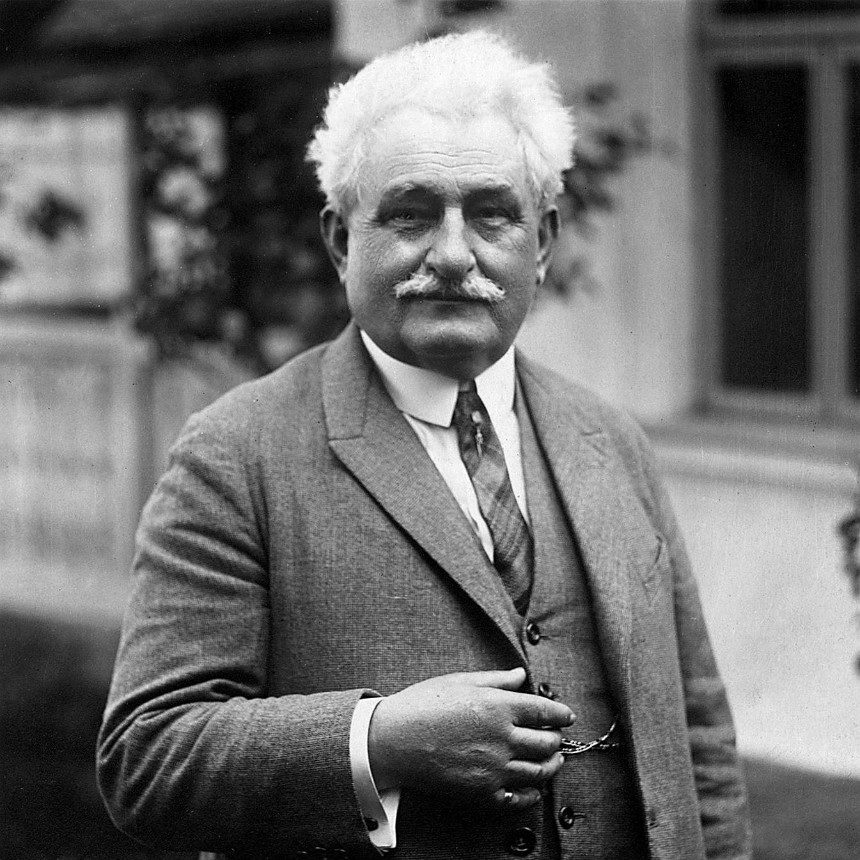

“I’ve been at the piano all week, composing and writing and laughing and crying, all at the same time,” wrote Schumann to his beloved Clara from Vienna in March 1839. “You will find this state of affairs nicely evoked in my Opus 20, the grand Humoreske.”

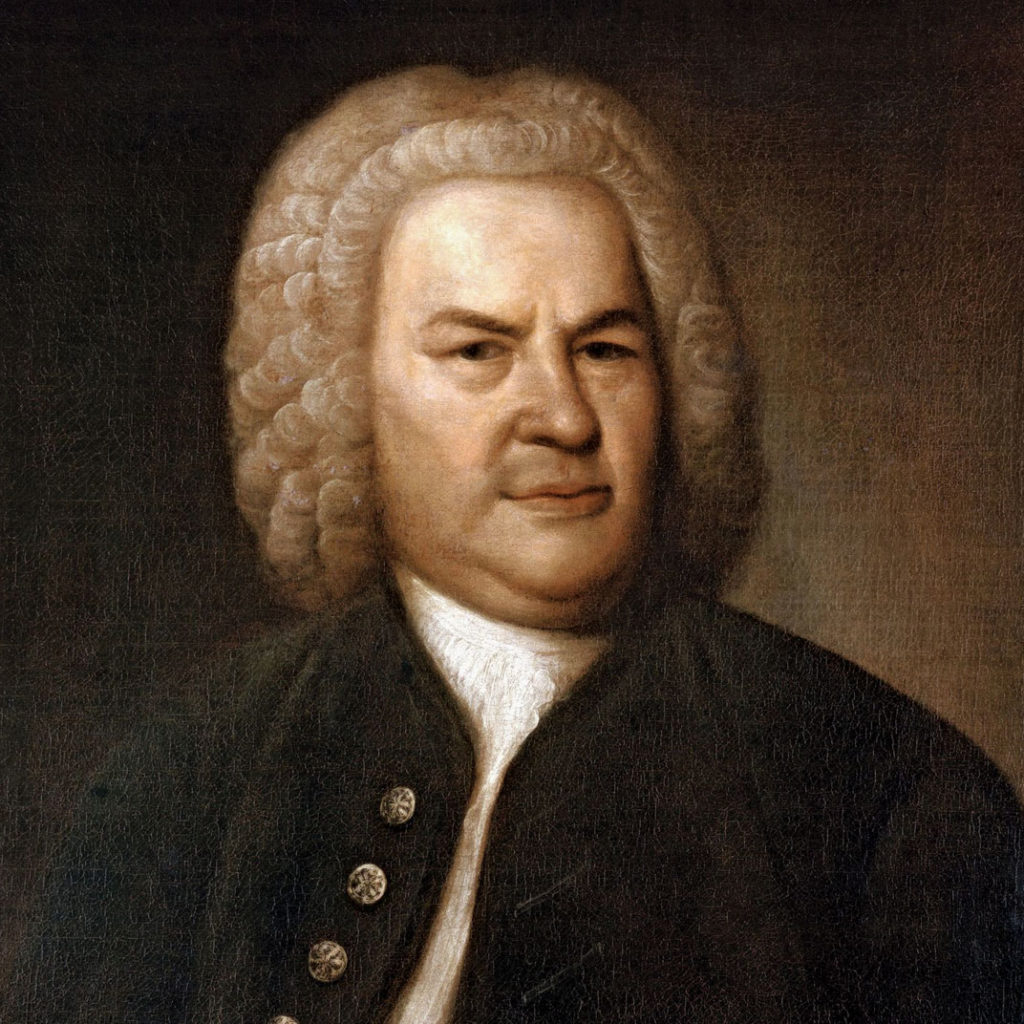

The Humoreske is one of Schumann’s most inspired creations. An elusive masterpiece, it is not one of his easiest works to follow, which may have contributed to its unjust neglect. Clara refrained from playing it in public, fearing it might be too inaccessible to audiences. In order to understand it, Schumann stressed that one must first have a feeling for Humor. The nineteenth-century German ideal of humour differs widely from our current English definition of the funny or comedic. Alluding to his literary idol Jean Paul, the German Romantic novelist from whom he “learned more counterpoint than from [his] music teacher,” Schumann described Humor as “a felicitous combination of gemütlich (genial) and witzig (witty).” We see this dichotomy reflected in Schumann’s famous alter egos: the sensitive and dewy-eyed Eusebius and the astute and often bitingly ironic Florestan. In his Vorschule der Ästhetik, Jean Paul ...continued